Poker & Pop Culture: The Thompson Street Poker Club

As poker clubs began to emerge in America toward the latter 19th century, stories about the games emanating from those clubs became a popular form of literary entertainment. Such stories also provide a glimpse into how poker was played, even in those cases when the stories are fictionalized or embellished.

Last week we looked at one collection of poker stories describing the adventures of an actual (though unnamed) uptown New York club of the late 1800s. Another interesting series of comic stories appeared a few years before that one, these telling of a fictional group of poker players called The Thompson Street Poker Club.

The Club's "Minutes" (with Illustrations)

Shortly after Life magazine first debuted in 1883, the magazine's associate editor Henry Guy Carleton began to produce a short poker tales focusing on the invented poker club.

The son of a famous Union general, Carleton was also a playwright who would later have a few of his plays performed on Broadway. He was additionally an inventor who is credited with early versions of smoke detectors and fire alarms.

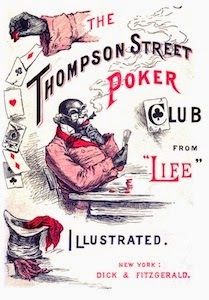

Carleton's stories about the club resemble colorful versions of the minutes of a committee's meetings, and they proved popular among Life's first readers. In the spring of 1884 a collection of 13 of Carleton's stories were published in a slim volume, titled The Thompson Street Poker Club.

The book was dedicated to Robert C. Schenck, referred to as "that noble expounder of the game." A former U.S. Congressman, Schenck earned that distinction thanks to his having written an early work of strategy about draw poker first published in England and reprinted in the United States in 1880 (a book we'll be discussing here soon).

A sequel penned by Carleton appeared five years later, titled Lectures Before the Thompson Street Poker Club and containing six longer stories featuring the same cast of characters. This one even more closely mimics the committee-meeting conceit, with each story starting with references to a speaker and those in attendance and even pointing out how the "minutes" of the previous meeting were read at the start of each new one. These lectures in the sequel sometimes recall incidents from the first volume, with the club's members revisiting earlier conflicts while debating the club's various rules and procedures.

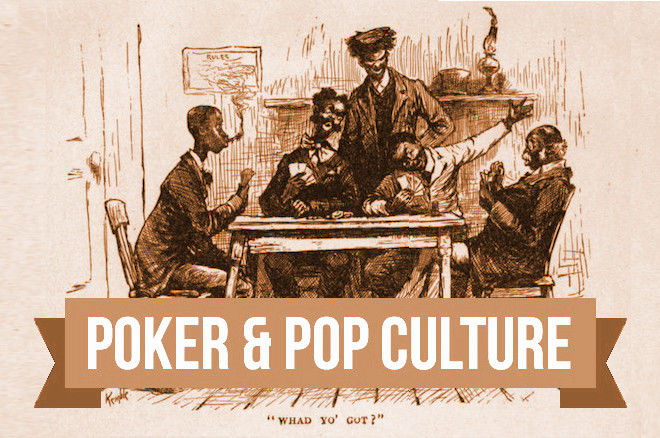

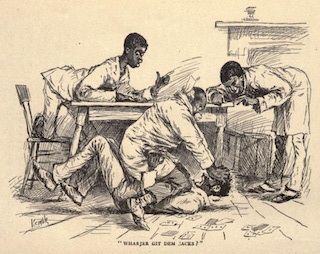

The Thompson Street stories are notable for a couple of reasons. One is the fact that they are illustrated with drawings by E.W. Kimble, best known for having been the illustrator for Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). In fact, it was after seeing Kimble's work in Life that Twain got in touch with Kemble and eventually got him to agree to draw illustrations for Huck Finn. (That's one of Kimble's illustrations for the book up above.)

Also noteworthy is the fact that the players in the Thompson Street Poker Club are African American, and thus the collections are often referred to as the first ever poker books to feature African Americans. They are also occasionally considered along with other late 19th-century examples of "black humor" or "slice of life" representations of urban blacks (albeit written and illustrated by whites).

Swapping Pots and Stories with Professor Brick, Mr. Cyanide Whiffles, and the Rev. Thankful

Reading through the two collections, the initial 1884 title contains many genuinely laugh-out-loud moments, as well as some very familiar scenarios from other poker fiction �� both before and after.

For example, one story titled "The Scraped Tray" reaches a climax with a draw-poker hand being bet and raised with all the two players possess, then ends with a showdown of four kings versus four aces, perhaps recalling the climactic hand of Mark Twain's story "The Professor's Yarn" first published right about the same time (not to mention many other quad-kings-versus-quad-aces stories.)

A twist here is the manner of the cheating involved to produce such a showdown �� one player has used a razor to scrape a three of diamonds to appear to be an ace. Indeed, the "razzer" is the favored weapon used to settle disputes in the games (unlike the pistol Backus draws in Twain's story).

In fact, the first story in the collection �� "Two Jacks an' a Razzer" �� might be read as a variation on the old Wild Bill Hickok story in which the lawman claims to have a full house with three aces and one six, then produces his pistol and announces "Here is the other six."

Of course, anyone who reads The Thompson Street Poker Club today is immediately struck by the sometimes-hard-to-parse patois devised by Carleton to represent his characters' speech and heavily employed throughout (again mimicking Twain). Such is evidenced in story titles like "Triflin' Wif Prov'dence," "Dar's No Suckahs in Hoboken," and "Dat's Gamblin.'"

The characters aren't too deeply developed although are suggestive of more thorough comic types, with Kemble's drawings adding a great deal to the reader's ability to imagine them. Most are given inspired names like Professor Brick, Mr. Cyanide Whiffles, Mr. Tooter Williams, Elder Jubilee Anderson, and the like.

The Rev. Thankful Smith is also a frequent participant, one of several churchmen who participate in the game. In one story the reverend finds himself involved in a humorous exchange about the relationship between poker and religion (or the lack thereof).

"I rises hit," announces the Rev. Thankful amid the play of a hand, who then "put up such a stack of blue chips that Mr. Whiffles nearly fainted."

"'What yo' go do dat for, Brer Thankful?' inquired the Deacon, in wild remonstrance. 'Dat's not de speret ob de Gospil.'"

"'Whar �� whar yo' fin' draw-poker in de Gospil?' testily rejoined Mr. Smith. 'Does yo' tink do Possles 'n de 'Vangelists writ de Scripter after rasslin' wid a two-cyard draw agin a flush?' he sarcastically inquired."

"'Dis ain't no prar meetin,''" Rev. Thankful adds by way of clarification.

I find the first collection of the two more engaging, and definitely recommend it to those who are interested. There's much more to say about them, as well as about their status as historical representations of blacks by whites (and more or less for whites) �� mostly sympathetic, though certainly of the era and thus unsurprisingly guilty of stereotyping and other negative connotations.

Later on the two Thompson Street titles would get sold along with another collection from 1888 titled The Mott Street Poker Club written by Alfred Trumble in which the activities of a group of Asian poker players in Chinatown are described (with markedly less racial sensitivity). Full-text versions of all three books can be readily found online.

Inspiration for an Early Poker Song

Also worth adding to the story of the Thompson Street Poker Club is a later allusion to the collection made by the Vaudeville performer Bert Williams, the first black American to star on Broadway. Among his many roles on the early 20th-century stage, Williams performed with W.C. Fields (also often seen at poker tables in his films) and with the Ziegfield Follies.

It was for the Follies that Williams performed a song he co-wrote called "The Darktown Poker Club" that proved a hit in 1914 and is certainly among the first-ever "poker songs."

"The Darktown Poker Club" is said to have been inspired by Carleton's Thompson Street stories, and the story it tells of a player complaining about cheating going on in a game fits right in with others in the collection.

Later the comedian and singer Phil Harris (voice of Baloo the bear in The Jungle Book) would cover the song in the 1940s, then the country star Jerry Reed (of Smokey and the Bandit fame) would do a version titled "The Uptown Poker Club" that proved a hit for him in the early 1970s.

The song tells of a character named Bill Jackson noticing all the cheating going on, and while sharpening his razor he decides to lay down his own rules for the game going forward:

"Keep your hands above the table when you're dealing �� please.

And I don't want to catch no aces down between your knees.

Don't be makin' funny signs or tip your hand

And I don't wanna hear no kind of language that I don't understand.

Stop dealing from the bottom, 'cause it looks so rough,

And remember that in poker five cards is enough!

When you bet, put up, 'cause I don't like it when you shy.

And when yo' broke, get up, and then come on back by and by.

Pass the cards to me to shuffle every time before you deal

Then there's anything wrong, why, I'll see.

Not gonna play this game no more according to Mr. Hoyle --

Hereafter, it's gonna be according to me!"

Here's a scratchy 78 of the song to listen to, if you're curious:

More next week regarding another notable poker club, a real-life one whose members came from one of the early 20th-century's most famous group of cultural influencers, the famed Algonquin Round Table.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America��s Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.

Be sure to complete your PokerNews experience by checking out an overview of our mobile and tablet apps here. Stay on top of the poker world from your phone with our mobile iOS and Android app, or fire up our iPad app on your tablet. You can also update your own chip counts from poker tournaments around ?the world with MyStack on both Android and iOS.