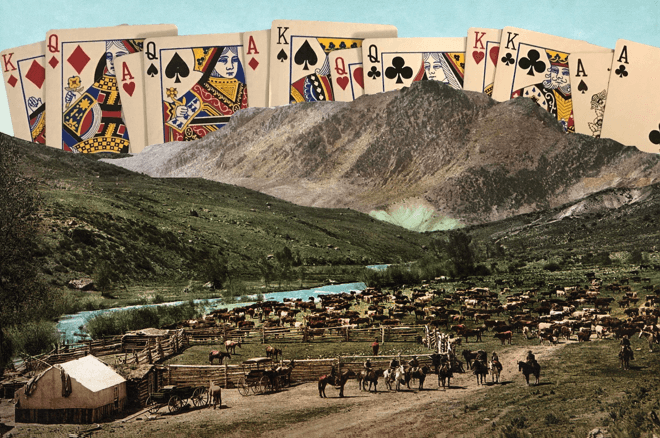

Fighting 'Range Wars' in Poker

I watch a lot of old western movies on Turner Classic Movies. The plots often involve a battle between homesteaders looking to divide up the open prairies into individually parceled out farms and ranchers looking to maintain the open prairie to allow for the free range for their cattle. Typically, this conflict of interests causes friction, often culminating in a battle between the two groups.

In the language of the time these battles were called "range wars."

In poker, "range wars" also involve battles of competing interests, but concerning very different kinds of poker ranges. These poker range wars are an attempt by one player to determine first an opponent's likely range of hands, and then how his own hand is likely to stack up against that range. The successful player must correctly assess how his hand compares not just to some specific hand, but to the full range of hands his opponent is likely to be playing.

Take for example a recent "range war" in which I became involved at a nearby poker room. I was playing $1/$3 no-limit hold'em. I was in the cutoff, and the villain was on my immediate left on the button. The game was fairly loose and passive, with lots of callers. By contrast, the player on my left regularly opened to $20, especially from late position, in an attempt to pick up all of the money from the callers.

In this hand I was dealt A?J?, and I called along with the four or five others. The villain on the button, as expected, raised to $20. Everyone folded back around to me.

I considered what the villain had. It would be impossible, of course, to put him on a specific hand. His range was enormous. It included every suited and unsuited connector, one-gappers, two-gappers, three-gappers, every A-x hand, and maybe every K-x, Q-x, and J-x, too, as well as all suited hands, and any two cards nine or higher.

He had not quite a complete stack of red chips behind, about $80 I surmised. When thinking about this huge range and how my hand compared to it, it made perfect sense to go to war with him �� either to get him to fold for a significant raise, or to have him fling in his remaining chips. So I raised him all in.

He called.

Sure, he could have turned over A-A, K-K, Q-Q, J-J, A-K, or A-Q and had me crushed. But I wasn't nervous. I knew that the vast majority of his likely hands he would play for a raise were either well dominated by my hand or, in the case of pairs tens or smaller, a virtually even proposition.

As it turned out, he was playing K?Q?, a hand on the higher side of his range. My A?J? won when the board completely missed both of us. But the specific hand and its result didn't really matter in my calculation. Since I judged myself to be well ahead of his range of not quite every two-card combination in the deck, my raise was correct, even if it had turned out that he had been playing the very top of his range with aces or kings, or if he had spiked a king or queen to win the hand.

A few hands later, I was in a similar situation with another player at the table. After a couple of players had called the $3 big blind I had raised to $15 in middle position with K?Q?. The short-stacked button called me and the action folded to the big blind who had not played a hand for more than $3 since she sat down 30 minutes earlier. I also knew that my image must have appeared fairly tight to her, as I had folded nearly every hand since she had sat down.

She three-bet me to $40.

I could not put her on a specific hand, of course. But I could put her on a range. Based on her position, her extreme tightness, and what I inferred was her understanding of my image, I figured that she must have had a very narrow and strong range �� probably Q-Q+, A-K, and A-Q.

In other words, her entire range was likely crushing me, and so I road off into the sunset.

As it turned out, the third player, who only had another $50 or so, went all in, she called, and her Q-Q lost to his A?10? when he made aces up on the river. My analysis had been correct, and I was pleased with having folded.

In the Old West, you had to view a range war as having the potential to be the one and only one you would ever have, since the consequences of losing were severe, permanent, and often fatal. On the other hand, the key to winning poker range wars is to understand that you're not focused on winning or losing one specific battle, but to consider the likely result of many contests over time.

You need to focus not on the one specific hand your opponents are likely to have, but the entire range of hands they might have, and judge how your hand stacks up against that range in the long run.

Ashley Adams has been playing poker for 50 years and writing about it since 2000. He is the author of hundreds of articles as well as Winning 7-Card Stud (Kensington 2003). He is also the host of poker radio show House of Cards. See www.houseofcardsradio.com for broadcast times, stations, and podcasts.

Image: "A cattle roundup in Colorado, c. 1898" (adapted), William Henry Jackson, public domain.